I recently had a small discussion with

some mates, when I said Braid was a superb game and I knew (I should

probably have said believed) The Witness would be just as enthralling as

the previous one, since Jonathan Blow seems to understand way better than most designers how the brain process

of "gratification" works. There was a bit

of an outrage. How could I be making such absolute statements? What

gives me the right to define "good" or "bad" games, when it's "a matter

of personal taste"?

|

| Banner of The Witness blog by Jonathan Blow / Thekla |

Some (way too many) people think of personal taste as some kind of obscure

magic that cannot be understood. In reality, taste is not that

unfathomable at all, being just another one of our many brain processes, and as

such, has both individual

and common elements. Our brain has evolved to find certain things

satisfactory, like the process of learning something new or any other

achievement, of which games and other arts should take benefit of. Of course, not absolutely everyone finds the same exact

things compelling due to genetic variability, which means we're not exactly as tall as our congeners, and our eyes not the same

color, but you won't find a 3 meter person or someone with pistachio

colored-skin. In fact, humanity is an incredibly homogeneous group, with

one of the smallest range of variations in DNA in the animal kingdom.

That, of course, also includes our brain, and with it, our tastes.

|

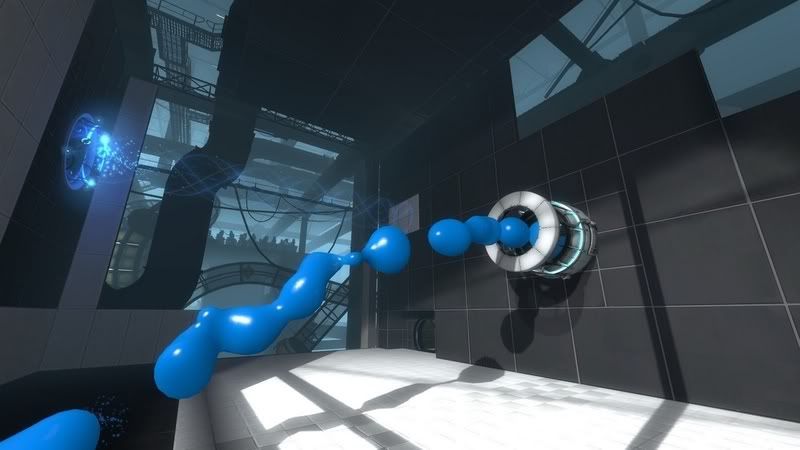

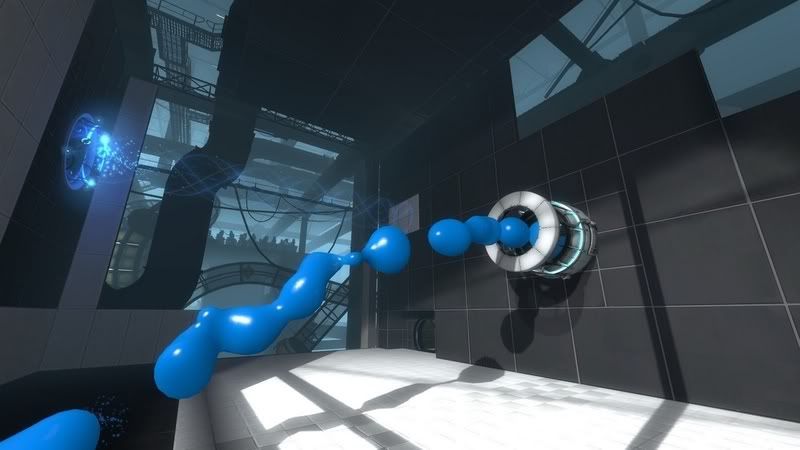

| Portal 2, by VALVe |

Whenever your game scores a 50 in Metacritic,

you are free to think that "it's just a matter of taste", and even

though you developed the game (or any other product or creative endeavor,

for that matter) according to your likes, it turns out that some people

liked it, and some people didn't, and it's just how things are. Ç'est la vie!

|

| An example of a lack of inquiry |

But then, you'll have to reconcile why, say, mostly every major VALVe game gets systematically scored near/over 90, under the same standards. It may be

some obscure bias in the press, or VALVe could own a crystal ball that

infallibly tells them what the public will like in the future, or...

could it rather be that the guys at VALVe, or Jonathan Blow, actually understand what the human brain generally finds gratifying? We could safely bet

their next game will have a similarly high score (time will give prove

me right!), and hey, prediction backed by results is engraved in the scientific process. Our head might not be

so dark and unique after all. Some seem reluctant to that idea, perhaps because that apparently "demeans" our uniqueness or

individuality. But we're not that unique at all, if you look into humanity from

afar, as a whole.

|

| A landscape painting by Victor Bykov |

It's a safe bet for anyone to say that "12 Angry Men" is an unarguably better movie than "Dragonball Evolution", even if they aren't remotely similar and even though a marginal group will object to it. Measuring objective quality might not be an exact science; it won't work 100% of the time with 100% of the products and people. Also, the best scale we currently have is Metacritic,

which isn't a perfect unbiased quality measure, but it is a somewhat reasonable numerical representation of quality. And yet, the results of scored objective quality have worked so well in representing human likes at a global scale, that it is naïve

and irresponsible to disregard them with the cop-out that "it's a matter

of taste", which has the same explanatory power than saying "it's

magic".

|

| "12 Angry Men" (1957) by Sidney Lumet |

There is a reason why there is a formal education, and a pool of information

on Fine Art, filmmaking or game design. There is actual

knowledge involved, or else you'd arrive to your music school

and be told to return home, since "well, it's a matter of taste, so who

knows?" (which is pretty much the postmodernistic relativist approach they take in modern "art" schools,

to my great frustration as an artist).

|

| Random crap I painted in 20 seconds or an abstract masterpiece? |

Actually, there are objective principles, like color harmony, or composition theory, that serve as tools for objectively good results, and they are taught

not because some guru decided to set a few rules, but

because all through the years of art history, cinema, or to a lesser

degree, game development (still in its infancy in terms of the available knowledge pool, but which can still greatly benefit from education

in other arts or areas), there have been people studying empirically

what satisfies most audiences and what the brain finds compelling, then

classifying it and turning it into manageable pills of actual

knowledge. It is a backwards process of seeing what people (generally)

enjoy, rather than some dogmatic set of rules you should avoid, as some people happen

to think.

|

Most of what we consider "modern" or "slick" follows

the "less is more" motto of the Bauhaus school |

In today's world, we more or less abide, and will probably will for many

decades onwards, by the principles of Bauhaus, school which

successfully studied the concept of elegance and packed it in a few basic concepts

(which game designers too often just haven't heard about) such as the

principles of "unity", "economy of means" and "form follows function",

which stand in our culture since the mid XX Century until today, and are as useful for a concept artist as are to a film director,

level designer or even a theoretical physicist. Anyone involved in a

creative process should have a full grasp of what the brain generally (not just his brain)

recognizes as "elegant" or as "gratifying", if he doesn't want to be

wandering, clueless about the decision-making process. The lack of that

understanding often leads to designers basing their decisions in an

erratic analysis of what they personally like, and often ends up in a

product that it's an uncohesive "frankenstein" monster of things they happen to like (but surprise, no one else enjoys the mix).

|

| Donkey Kong Country Returns, by Retro Sudios. A game that understands players and design foundations. |

The reasons

why people like or dislike a game (or movie, or

painting) are specific, traceable and understandable, even though the

main public is not always conscious of them or knows how to

analyze those emotions or verbalize the concepts. It is our job to read between lines and understand what "clicks"

in their head giving their brain that injection of

dopamine/

serotonin

that stimulates their mental

reward system and ends up in them "liking

the game".

Games, more and more every day, blatantly ignore this process

and reduce

the act of playing to a series of "obeying prompts" (Hold "E" to plant

the bomb, or the candidate to lamest game mechanic ever: the new "gap-jumping"

context-sensitive action in Mass Effect 3). This "trend" shows a dramatic

disregard for knowledge of what makes the brain feel a sense of

accomplishment. For example, the off-game interaction between friends

playing together in the couch is seldom considered in the design

process, and yet it's one of the strongest emotional grips a

game can provide, and often catalyzes our fondest game memories.

|

World of Warcraft, by Blizzard Entertainment, a game often cloned

without an in-depth understanding of what it made right.

|

Way too often, when

a game is succesful, developers or publishers simplify the

data to something like

"they

liked GameX, therefore they are going to

like my interpretation

of GameX", neglecting in the process the real underlying reasons

why GameX's formula worked. Soon after, surprise

comes when their clone of GameX is not remotely as succesful as the original one, not just

in terms of sales, but of quality overall. This way of doing things is a dead end.

Much of this rant will be quite obvious or even intuitive to a lot of

people, yet the actual games themselves suggest that it might be a riddle to many, not just amateurs, but actual professionals. Understanding a bit of psychology perhaps seems like a somewhat "fringe" topic for a

creative person, but it happens to be

so dramatically important when your work is made for others. In most cases it could be laziness, but it's

sometimes something a bit more dangerous. As Stephen Hawking put it "the

worst enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, but the illusion of

knowledge".

|

| The World's best paid artist, Damien Hirst, with one of his pieces. |

Let's please get rid of this idea of taste being something

that mysterious or personal; there is only a small part of that. I believe there are many rewards to be found in educating the public (and very specially the press) on the difference between what's well done and what you

like. And please, the next time you attend to an exhibition by Damien Hirst, tell the audience on my behalf that it's not "a matter of taste", it's just a consented scam.

P.S: I'm hardly a writer, so it's challenging for me to structure all this

information (excuse if it's confusing or drifts too much, please say) specially in a foreign language.